TEETH ASK THE BIG QUESTIONS

1. If I could be anything other than what I am, a middle-aged Jewish writer with abs like a bucket of slops, I'd be an orthodontist. They move teeth. They look inside you with little mirrors. They make machines and sculptures for the inside of your mouth. You are part of a ritual.

2. I once wrote a story where I slept with the Tooth Fairy. She was better than Mrs. Santa or Peter Pan. Nighttime and she flutters into your house in a pink tutu and waves a wand over your sleeping children. She leaves them coins and takes their teeth back to her moist mouth-red cave. How is it this femme fairy crosses from the toothy beyond and enters our home?

3. Teeth exist at a gateway between some kind of unconscious experience, something on the edge of the psyche, and everyday life. They are also wonderfully absurd. When at the dentist, my mouth gurgling and full of instruments, the dentist picking at things and speaking a strange dental Kabbalah to the assistant, I wonder if the whole experience is not medical at all, but really a complex performance-art piece performed at the expense of the patient/audience. Maybe the dentist will pull an endless series of knotted handkerchiefs out of my mouth, or a bouquet of flowers. Maybe she will chant the 32 names of God, the 32 counties in Ireland or the number of chess pieces, both white and black.

4. When one of my sons was three or four, he worried about his own safety.

Nighttime: “Help,” he calls from his bed. “The earth is going to be destroyed.”

“Don’t worry,” I say. “The earth is really really big and very very strong.”

“But the sun is going to get huge and burn everything up just before it collapses and the Solar System becomes very cold.”

“True, but it won’t be for another five billion years.”

“So the earth is going to be destroyed? Help!” And so on into the night.

5. When my son was four he worried that our house could be infiltrated, that “the perimeter was not secure.” If the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus could get in, then so could ghosts, goblins and boogiemen, not to mention evil creatures that had neither name nor shape.

We told him these things were invented for the delight of children. Joy. Wonder. Imagination. Thrills. They were what made for a rich and fulfilling childhood. His childhood. But we also told him not to reveal the secret to his little brother and sister or else, made-up or not, these good inventions wouldn’t bring gifts for him. And thus it was that the Tooth Fairy hung up her tutu and wand and he was financially rewarded for the loss of his teeth in a more mundane transaction, a quarter with a caribou head slipped beneath his pillow by one of his parents as he slept. If we remembered.

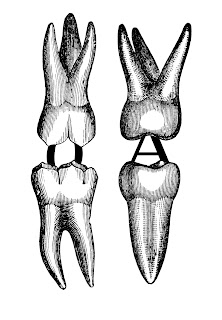

6. The alphabet is connected to the mouth, to the tongue, to the place where the sounds, particularly the consonants, are formed. Teeth invoke speech, the primal experiences of reality, childhood, and the oral, but are also resonant archetypes from a parallel alphabet. There’s a connection between teeth and the alphabet, between teeth and the keys of a typewriter.

7. A lost tooth is a letter, a sound, a meaning extracted from the mouth, fallen. It is a sign out of place, removed from the locus of signification, from the place of utterance. It becomes itself, its own talking head. It is a tiny megalith, a dental henge, a miniature inukshuk. A prize from the Kinder Egg of the mouth.

8. I’m at the dentist, lying on my back. I see angels. The dentist has taped a poster of Rafael’s cherubs on the ceiling. Faces hover over me. How many? I can’t see. There are many gloved hands. There’s muttering. My mouth is stretched open and a tube makes gurgling sounds as my saliva is sucked out. There are drills, mirrors, picks, a hook pulling at my cheek. The dentist and her assistants peer into this wide gap in my head as if looking into a sinkhole or a mineshaft where rescued workers are expected to emerge any moment. “They’re safe. Thank God.”

9. The dentist and her assistants speak to each other, and sometimes to me. They’re all Polish and so there’s the soft susurration of consonants. Uhh, uhh, uhh, I respond. They speak of higher levels of consciousness. Night. My teeth. Shadows in the forest. What is inside is out. They have crossed the threshold. The perimeter is not secure. The portal between the world and my body has been opened. Hand passes over hand, an assistant passes an instrument to another, a cavity has been found, the drilling begins.

10. A tooth is part of the body but not. It is neither flesh nor bone but something else. We humans are soft but here in our softest place, we have a kind of antler.

11. Because of this, teeth ask the big questions: What exactly is the body? How do we live on earth? What is the world and what is us? How is our body infused with our mind, how does the mind entwine with the physical world?

12. We are born without teeth, or rather, the teeth are hidden. Treasure teeth. Then they break our skin, emerge like new shoots from below the earth. We cry. Then soft as milk, they fall from our mouths. New teeth grow, budding leaves on gum limbs.

13. How much of our body grows after we’re born? Hair, nails, teeth. Tumours. The fontanels of the skull. How our body changes. Skin. Wounds. Moles. How we get larger or smaller, fat, shrinking bones, muscle. Accidents. Amputations.

14. My wife used to dream her teeth were falling out. She used to imagine teeth raining down around our bed like hailstones. After the car accident I had when I was 16, when I fractured my spine, I dreamt my vertebrae a tower of teeth, each tooth stacked on another. And then my body collapsing as the teeth were pulled out, a disembodied dentist yanking with pliers.

15. Baby teeth, the first set of teeth are called deciduous teeth. Most mammals have these temporary teeth, but not elephants, kangaroos, or manatees, whose teeth are continually replaced.

16. Last night, my son told me that he’d kept the baby teeth from Dude, the dog he’d had since he was little, now buried in our yard. I have some baby teeth my mother-in-law kept from when my wife lost them but I’ve lost our children’s baby teeth and the Tooth Fairy isn’t returning my calls.

17. I love that teeth develop in embryos, tiny little fishy fists with buds in their tiny gums. Buds which erupt into the twenty teeth babies have after they’re born. Teeth growing in the dark. In utero. Cave creatures, pale, hidden.

18. Most adults have 32 teeth. Our alphabet used to have 32 letters. We lost some, like unneeded teeth. Chew on these: Eth. Yogh. Thorn. Wynn. Ash. Ethel. Ten fingers, ten toes, ten holes in the body and thirty-two teeth. Thirty-two feels like right number. The thirty-two piano sonatas of Beethoven. The thirty-two five-dimensional crystal families.

19. I had to look up how many holes are in the body. Eyes, Ears, nostrils, mouth, anus, urethra, vagina. Eleven. Remarkable that I couldn’t think of them off-hand but it depends how you count. Eye holes? Umbilicus? The pores of the skin? I’m thinking of how the body is open to the outside. Of course, the body is made of the outside. We’re in a constant exchange. Food. Air. Water. Minerals. Chemicals. Radiation. Waves. What is the exchange value of the body? How are we monetized? How do we refuse?

20. I also looked it up and there are thirty-two Kabbalistic paths to Wisdom. I had my wisdom taken out when I was twenty.

21. Dentistry, like the Kabbalah, at least as I experience it, is pataphysical. An arcane hieratics of signs and rituals. A choreography of solutions. A hermeneutics. Jokes, like essays, are pataphysical, also. Self-sufficient worlds invented to move about in and solve their imaginary conundrums.

22. One way my dog or my toddler knows things is by biting them.

23. Once as I was sitting on the floor, my mother-in-law’s teacup poodle bit my penis. I did not know I could move so fast. Now the poor dog has no teeth and so, with nothing to fence it in, its tongue lolls out of its mouth.

24. Baby teeth, the first set of teeth, are called deciduous teeth. Leaves on the tree of the mouth. Most mammals have these temporary teeth, except not elephants, kangaroos, or manatees, whose teeth are continually replaced. What in my body is replaced—skin, hair, nails. What else?

25. When my wife was a girl, she knew that the Tooth Fairy wasn’t real. She knew it was really her big tall dad who took the teeth and put the silver under her pillow. But she’d seen a pink tulle dress and a tiara in her mother’s closet and assumed that this is what her father dressed up in, adding a star-tipped wand to perform the job of Tooth Fairy.

26. Under the pillow, no more teeth. A handgun. The perimeter is not secure.

27. Last year, I ordered several sets of plastic teeth from China. My plan was to replace the keys of a typewriter with teeth. Then I realized it’d be better to glue teeth to each individual strikers in the semi-circle of strikers. Then typing is like biting, writing is like gnawing the page. Teeth marks instead of words.

28. I had braces twice. The first time, when I no longer needed to wear my puck-sized retainer, I drove over it with the family car until nothing but pink dust remained. The second time I was in undergrad and went to the Canadian National Exhibition on a third date with a woman who would end up being my wife. We rode the Flyer, a rickety wooden rollercoaster. At some point, my braces got stuck on the fluffy 1980s sweater my date was wearing. She assumed that I was terrified as my head was firmly planted on her shoulder for the entire ride. Only when the ride ended, was I able to untangle my braces from her sweater. She married me anyway.

29. When we look at a tooth, it is a sign, a signifier, and not the signified. When we look at the body, it is as if we are looking into a massive dictionary. Under “teeth,” there are many definitions, and its various meanings can be cited from contexts throughout history. We can’t look at tooth, or at anything at all, and see some objective and pure notion of that tooth or that thing.

30. Another story that I wrote was about the dentures of a man who died, left in the glass beside the bed. Before sleep, his wife would turn to them and say goodnight. Then one night, the teeth began to move—to snap open and closed in a waltz rhythm. One-two-three, one-two-three. And so the wife began to dance with the teeth of her late husband, waltzing around the room.

31. A writer looks inside you with little mirrors. They make machines and sculptures for the inside of your mouth. They move teeth. You are part of a ritual.

32. We include and resist by writing.

Comments