Creating a Treasure Map: Trying to draw the two-dimensional roadkill of a sorcerer’s dreams

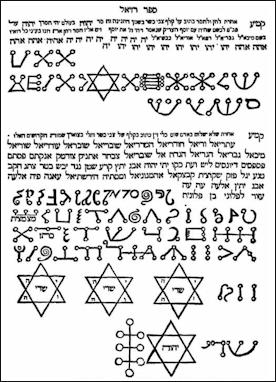

I've been trying to make a treasure map for Yiddish for Pirates, my pirate novel. I wanted it to have the right admixture of mystery--arcane Kabbalistic symbols, Hebrew letters, sea monsters--old fashionedness, and wonder. And a kind of submerged piratical humour. I'd like it to have some cryptic clues, jokes, or red herrings (or at least flamingo-coloured smoked salmon.) Also, it should riff off the Treasure Island map that Robert Louis Stevenson created for his novel because my novel borrows many elements of the descriptions of that map and the search for the treasure from that classic tale.

I haven't yet been successful.

Above is Stevenson's map, stripped of all the place names and with a newly made compass rose. I had planned to add all the elements above, but I'm thinking that even with these it won't be as interesting as the map suggested in the text. I'm wondering, if I should actually try to represent the map that I describe. Now that I try, I'm feeling that describing something but not showing it creates more mystery and wonder. The suggestion is more powerful than the realization. Perhaps a countermap is less powerful than the described "counterfactual imaginary." Like making a movie out of a book in some cases.

But maps in books are always beguiling. I remember as a child discovering the map in front of The Hobbit. The clear line of the mapmakers/ hand. The contrasting red elements. The drawing of the pointing finger. The unintelligible but powerfully communicative script. I'd return to the map during readings of the book, realizing what it was about, using a key to decode the runic. The map which strongly evoked the world and sensibility of the novel.

But maps in books are always beguiling. I remember as a child discovering the map in front of The Hobbit. The clear line of the mapmakers/ hand. The contrasting red elements. The drawing of the pointing finger. The unintelligible but powerfully communicative script. I'd return to the map during readings of the book, realizing what it was about, using a key to decode the runic. The map which strongly evoked the world and sensibility of the novel.

Below are the bits where my imaginary map is described. There are also images which I hoped to plunder or be inspired by for elements of my map.

There was much we recognized. The broadside islands of Hispaniola and Cuba with their fussy ongepatshket shores. And below, the pokey little skiff of Jamaica rowing up from the south. And above, the pebble-scatterings of the Bermudas, like stepping stones to nowhere.

The map was the two-dimensional roadkill of a sorcerer’s dreams, a brainbox of arcana pressed into two-dimensions against the vellum. Archipelagos of eyes, cluttered across the Caribbean, their preternatural gaze drawn as radiant points of a compass rose beaming across the sea. An undulating dolphin-dance of Hebrew script twisted between inky waves. And curious sigils, perhaps from Solomon’s time, marks of demons, angels, cartographers, or whorehouses flocking like alchemical birds on both land and deep.

It was more-or-less apple-shaped, about three leagues across, and had a shaynah fine natural harbour where we could drop anchor. There were, as Moishe had remembered, two enticingly zaftig hills, like the twin knaidlach of a rotund tuches, which dominated the island. They were farprishte-poxed by three marks in red ink: one on the north part of the island, two in the southwest. Moishe explained that they were Hebrew letters. Hay. Vav. Hay. In a valley in the centre of this triangle was a small, neat letter Yod written in the same red ink . Buried beneath it: the books. Once we had found the island, and located the valley, we would know where to go. The tree must be the Yod.

Comments